OAKLAND, Calif.—Eighteen months ago, when Jimmy Duong’s doctor advised him to have surgery for a torn ligament on the pinky of his right hand or face the possibility of chronic pain and swelling, Duong, then 22, chose the less expensive option.

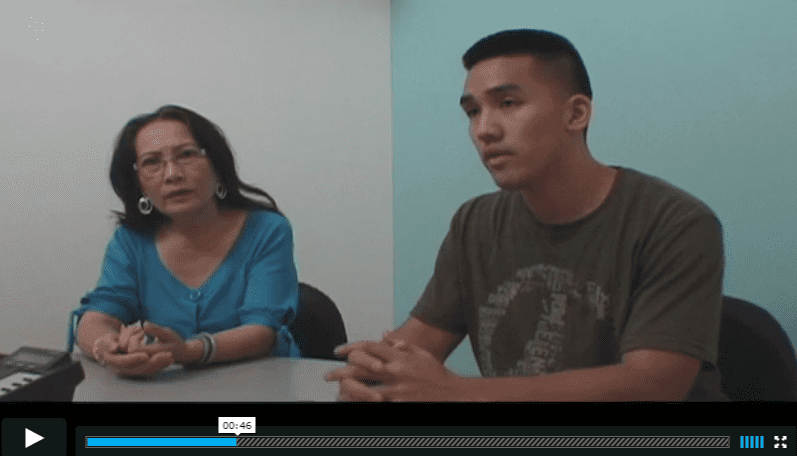

“Surgery would have cost more than we could afford,” he said, as he sat in his mother’s office at the Asian Health Services here. His mother, Alisha Nga Tran, is a community health advocate at the clinic.

Duong held up his pinky. It was swollen and a little crooked. He said he endures constant pain. “I wish I had had health insurance.”

Come Thursday, key provisions in the new health care reform law will take effect, significantly altering the health care environment by providing greater access to coverage to hundreds of thousands of Americans.

One of those provisions would allow adult children like Duong to stay on their parents’ employer-based insurance plans until they turn 26.

It doesn’t matter if the child lives with his or her parents, attends college, receives financial support from them, or is a dependent for income-tax purposes. Nor does it matter whether the child is married or single.

Health care advocates and providers welcome the provision. “We have a ton of children [here in the Central Valley] who will benefit from this,” said Kevin D. Hamilton, chief of programs at the Fresno-based community health clinic Clinica Sierra Vista.

“Youngsters typically enjoy good health, but they can develop unexpected diseases,” said Dr. Ricky Choi, head of pediatrics at Asian Health Services. “There are many unexpected health issues, not to mention accidents, that can happen at that age.”

Hamilton said that he knows of many middle-class families who “kicked their children out of their homes” as they turned adults because they could no longer afford to keep them at home or on their health insurance plans.

Young adults, more than any other age group, are the most likely to lack heath insurance, many surveys show.

According to the U.S. Health and Human Services Department, some 1.2 million young adults are expected to benefit from this provision in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA). Gerald F. Kominski, associate director of health policy research at UCLA, estimates there are around 1 million uninsured young adults in California.

The rules generally take effect for insurance plan-years that begin on or after Sept. 23 this year.

However, the rules allow an exception for employer-sponsored health plans that were in existence on March 23, when President Obama signed the health care bill. In general, such health plans can exclude adult children of workers until 2014 if the children have access to insurance through another employer-sponsored health plan. For example, if Duong finds employment that offers him health insurance, his mother’s plan will not have to cover him.

Under the new rules, insurers and employers must provide young adults with a 30-day opportunity to enroll in their parents’ coverage. Terms of coverage cannot vary based on the age of young adults under 26. An insurer who imposes a surcharge on premiums for children aged 19 to 25 would be in violation of vthe law.

The cost of the new provision will be borne by all families with employer-sponsored insurance, with family premiums expected to rise by as little as 0.7 percent, according to Linda Leu, a policy analyst with Health Access, a California consumer advocacy coalition.

“On average, adult children between 19 and 25 are the least expensive adult category to insure,” Kominski said. “So the cost of adding adult children to a plan will not be a huge expense.”

Many insurance companies began voluntarily offering dependent coverage within weeks after the law was signed, and some employers began notifying their employees about the new benefit. Tran said Asian Health Services has already begun the paperwork for her as well as for other employees with adult children.

Tran, who came to the United States in 1981 as a refugee from Vietnam, said she is both relieved and overjoyed about the provision in the law. Since her husband died four years ago from a heart attack, she has been single-handedly raising her three children on her $38,000-a-year salary.

Her son, Duong, was on her health care plan until he enrolled in UC Berkeley at age 18. While there, he had student health insurance, but when he graduated at age 22, he couldn’t get back on his mother’s plan because he had “aged out.” Currently, most health insurance policies allow parents to keep dependent children on their plan until they graduate from college, or if they are not enrolled in college, until age 19.

“It’s hard for me to buy insurance for my children,” she said, noting that she’s always worried if her children are genetically predisposed to high blood pressure and high cholesterol, which her husband had suffered from since his 30s. “I’m very, very happy the law begins tomorrow.”