New grant from Kaiser could help more Oakland residents manage chronic illnesses

Posted

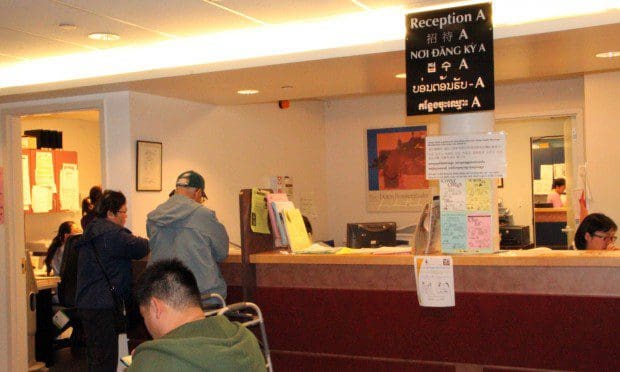

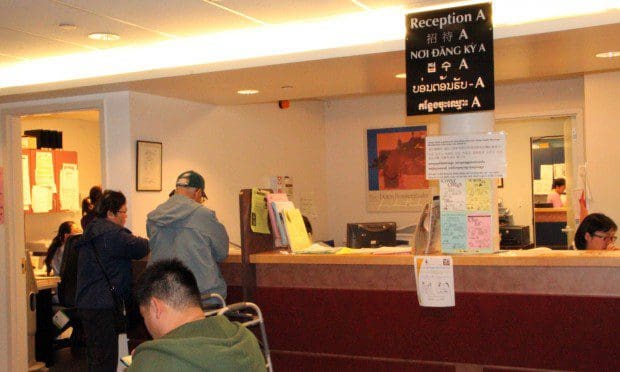

The patient could have easily slipped under Dr. Steven Chen’s radar. Like many of the diabetics he treats at Asian Health Services, a community health center located in Oakland’s bustling Chinatown district, the woman was in her late 50s, spoke primarily Mandarin and only visited the clinic once every few months for checkups.

However, as part of the center’s health coaching program, she received regular follow-up calls from medical assistants trained to monitor patients between appointments and ensure they are following doctors’ orders. Through an early follow-up call, the health coaches discovered Chen’s patient was experiencing dangerously low blood-sugar levels at night, a sign for Chen that he needed to decrease her dosage immediately.

“I was able to catch it within a week instead of three months later,” he said. “I think any time that a patient has a side effect from any medicine or a new approach and they have someone they know they can go to or they know some is going to call them, that helps them adhere to their medication or lifestyle plan.”

A new round of funding from Kaiser Permanente, just announced today, could allow more of Chen’s patients and other low-income and uninsured Oakland residents receive help managing chronic diseases, like diabetes. The $5.1 million investment will benefit community clinics and public hospitals, often referred to as the “safety net” providers because they provide health services to patients regardless of limited financial means or insurance coverage. Grants ranging from $150,000-$200,000 will be awarded to sites throughout Northern California, including several in Oakland like Asian Health Services.

AHS will receive $150,000 to expand its current health coaching program to include a Kaiser-developed program called PHASE—Prevent Heart Attacks and Strokes Everyday. Implemented in community clinics and public hospitals since 2007, the program incorporates medications and lifestyle changes to reduce the risk of heart attacks and strokes.

“The [PHASE] program is derivative of what we do for our own Kaiser members, which is aggressively identifying patients who are at an increased risk of heart attacks and strokes and providing drug therapy and behavioral self-management support,” said Dr. Winston Wong, medical director of Kaiser’s community benefit program and a long-time AHS volunteer.

PHASE could be especially beneficial to the community AHS serves, according to Chen. “I think the exciting thing is expanding on a model that’s already been co-created with Kaiser’s help and now we’re really able to take it to another level and expand,” he said. “No matter how much I spend time explaining a medication, sometimes a patient will reveal things to the health coach they won’t reveal to us because of our white coats. This kind of innovation being supported by Kaiser is really helpful because we really think this should just be a part of routine care.”

AHS has been using the PHASE model for diabetic patients like Chen’s for about three years, but with the new Kaiser grant, the center will have funds to hire new staff and extend the program to all patients at risk for heart attacks or strokes.

“Working with diabetics, I see it definitely has benefits for patients, so if we can expand this program into cardio patients, it would be good,” said Mariana Chang, AHS’s chronic care assistant responsible for overseeing the health coaching program. “It’s always great when a patient calls and they actually know which health coach to look for if they have an issue about medication or an appointment change.”

Three medications are fundamental to PHASE: an ACE inhibitor, which treats high blood pressure; a statin, which lowers cholesterol; and aspirin, which is associated with a lowered risk of heart attack and stroke.

“The grant is for organizations like Asian Health Services to put this program into their regular clinic practice and to enable them to more effectively identify those patients who would most benefit from these drugs,” Wong said.

The medications are not considered a cure-all, however. “We’re not putting everyone on these drugs,” Wong said. “The criteria includes diabetic patients 55 years and older and those patients that have already had a history of coronary disease including maybe even a previous heart attack.” According to Wong, the criteria are based on an assortment of published medical studies on heart attack and stroke prevention.

Behavioral changes are also an important component of PHASE. “Obviously, for those smoking or using tobacco, that’s the number one kind of intervention that should take place in addition to putting them on the three drugs,” Wong said. The health coaches also encourage low-fat, high-fiber diets as part of PHASE and moderate, daily physical activity like walking.

“We have to individualize it because some patients shouldn’t be on aspirin or shouldn’t be on a statin because they’ve had side effects and the data’s not going to capture that,” Chen said. “If I can get better results from lifestyle changes instead of relying on a drug or statin, so be it—it’s better for the health care system, better for my patients and better for me.”

Chen’s patient-centered approach is a method he believes is integral to the work AHS does and programs like PHASE are vital to this treatment process. “A lot of our patients come from countries where authoritative governments or institutions have really battered or oppressed them, so that’s kind of the context in which we work,” he said. “The traditional model has been, ‘I’m the person of authority—do this, this and this.’ The paradigm shift is to say, ‘How do we increase patient self-management and have patients drive the change they want to see?’”

Chen said connecting with patients is important to he and his colleagues, many of whom have long histories with AHS and strong ties to the community. Chen has been with the center for eight years, and Chang six.

“Growing up here in Oakland, I definitely feel like it’s my duty to give back to the community,” Chang said. “It’s something that I want to do and something I have a passion for.”

Chen said he feels a strong connection to the community he serves. “I’m a child of immigrants,” he said. “A lot of my patients I really see as similar to my family members—the struggles around navigating this maze we call health care and the challenges around that and how so many things get lost by language and communication. I just thought, if I can take care of my parents and family members, I should be able to do the same for my community.”

Wong’s history with AHS dates back to his days as a UC Berkeley student in the 1970s. After volunteering with the organization, he became a board member, then later a staff physician and eventually the medical director. Since coming to Kaiser, he has maintained his involvement with the center, still volunteering time to care for diabetic patients.

“The lack of bilingual, bicultural health care was an unknown story back when I first started volunteering,” he said. “Low-income, immigrant Asian communities were not thought of as being medically needy and I felt that that was important as a professional to see myself providing care where care was most needed. Now I think issues around health care in Asian communities are better known, but an important need is still there. I derive a lot of strength and lessons from the community.”

Chen believes that with continued support from Kaiser, AHS will successfully serve more patients like the diabetic woman he saw benefit from PHASE health coaching. “There have been so many other shifts in her life that are moving towards a positive,” he said, referring to the team-based approach he feels is responsible for the changes. “I think she’s really appreciated the multiple touches.”