IMAGINE THAT you have multiple chronic health problems: diabetes, heart disease, hypertension and high cholesterol. You also run a local business that supports your whole family.

Now imagine that you have a choice: You can either keep running the business or get the health care you need — not both.

It doesn’t seem like a choice anyone should have to make, but that’s exactly what a Korean-speaking woman I met at Asian Health Services faced. She lived in Contra Costa County, where there was no clinic or hospital that provided an interpreter, even though all are mandated to have one by state law. She knew that with her health history, understanding the doctor, pharmacist, and other staff was crucial. So, she closed her family business and moved — just for the care at our Alameda County clinic.

Unfortunately, this woman’s story is something we see here in various forms almost every day. Patients come in from all over the Bay Area when they can’t get linguistically or culturally responsive care elsewhere.

So what does this mean for those who don’t come through our doors or who need specialty services that we don’t provide?

Some patients try to make do on their own. This can lead to complications — like the patient who only understood the number “81” on his prescription and took 81 pills instead of one that contained 81 milligrams. He ended up in the ER and could have died.

Some have their children interpret, creating dangerous situations for the whole family when the children can’t or don’t deliver embarrassing or bad news to their parents. Other patients get so frustrated that they just go home without getting the care or medications they need.

The 2010 Census shows that this problem will only get worse for Asian-Americans, California’s and Alameda County’s fastest growing population. Other minorities, like Spanish-speakers, face similar situations.

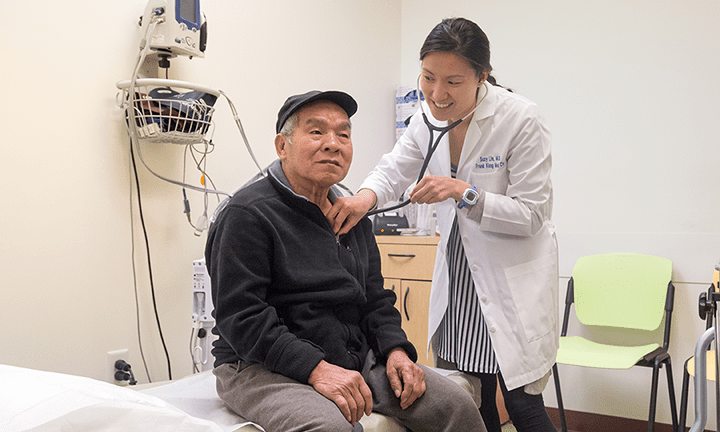

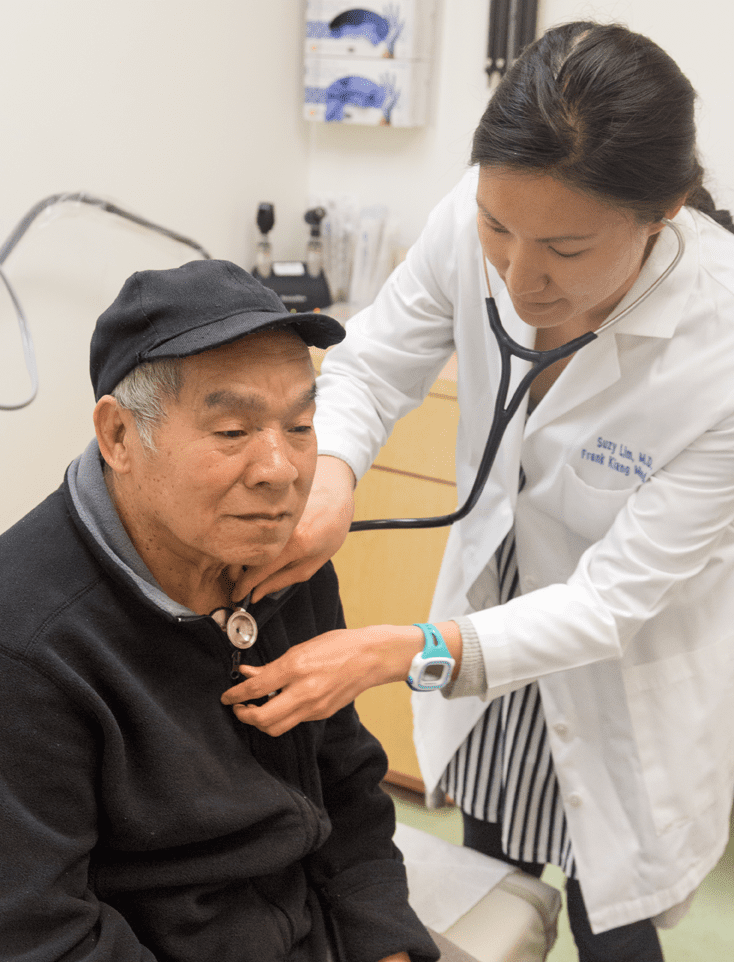

The good news is that all health providers are mandated to offer certified medical interpreters, like myself. I speak English and Korean and have been trained to interpret medical terminology and look for cultural cues that average workers may miss.

The bad news is that there is little to no monitoring or enforcement of SB 853, the 2009 law that requires insurers to only work with facilities that provide interpreters. That should change.

We also have a huge opportunity before us. Economists predict that California will need to dramatically increase our numbers of doctors, nurses and allied health workers. This was a need before health reform, which will greatly expand the number of insured Californians.

As providers ramp up this recruitment and hiring, how they train workers is critical for providing culturally responsive care. It’s not just about language — although that is crucial — but rather understanding a patient’s specific needs and handling their care in a sensitive, knowledgeable way.

I hope for the day when patients don’t need me or Asian Health Services because they get the same culturally competent care by their provider. But we have a long way to go. If we continue on this path of cultural and linguistic mismatches between health workers and patients, examples like the one above will not be simply something to imagine but rather, sadly, a reality for more and more patients in need.

Jinyoung Chun works for Asian Health Services as a certified medical interpreter and is the site manager for the Frank Kiang Medical Center in Oakland.